At this moment in time, in what I would refer to as the "Thielian moment", we witness a culmination of tech cornucopia narrative reckoning with the fact that progress is neither unconditional nor real.

Some people in crypto (and tech) expect too much of the technology. They also might have a skewed perception of progress. An opportunity to organize my thoughts around this topic presented itself when I found myself writing a review of Chris Burniske's essay A Blank Slate of State.

This essay paints a darker version of the future in comparison to Burniske. I think that the desired Blank Slate of State is a pipe dream. Lumping technological advancement with a general notion of progress is treacherous.

Progress is a beguiling call to death and we're addicted to the sweet pitch of its siren.

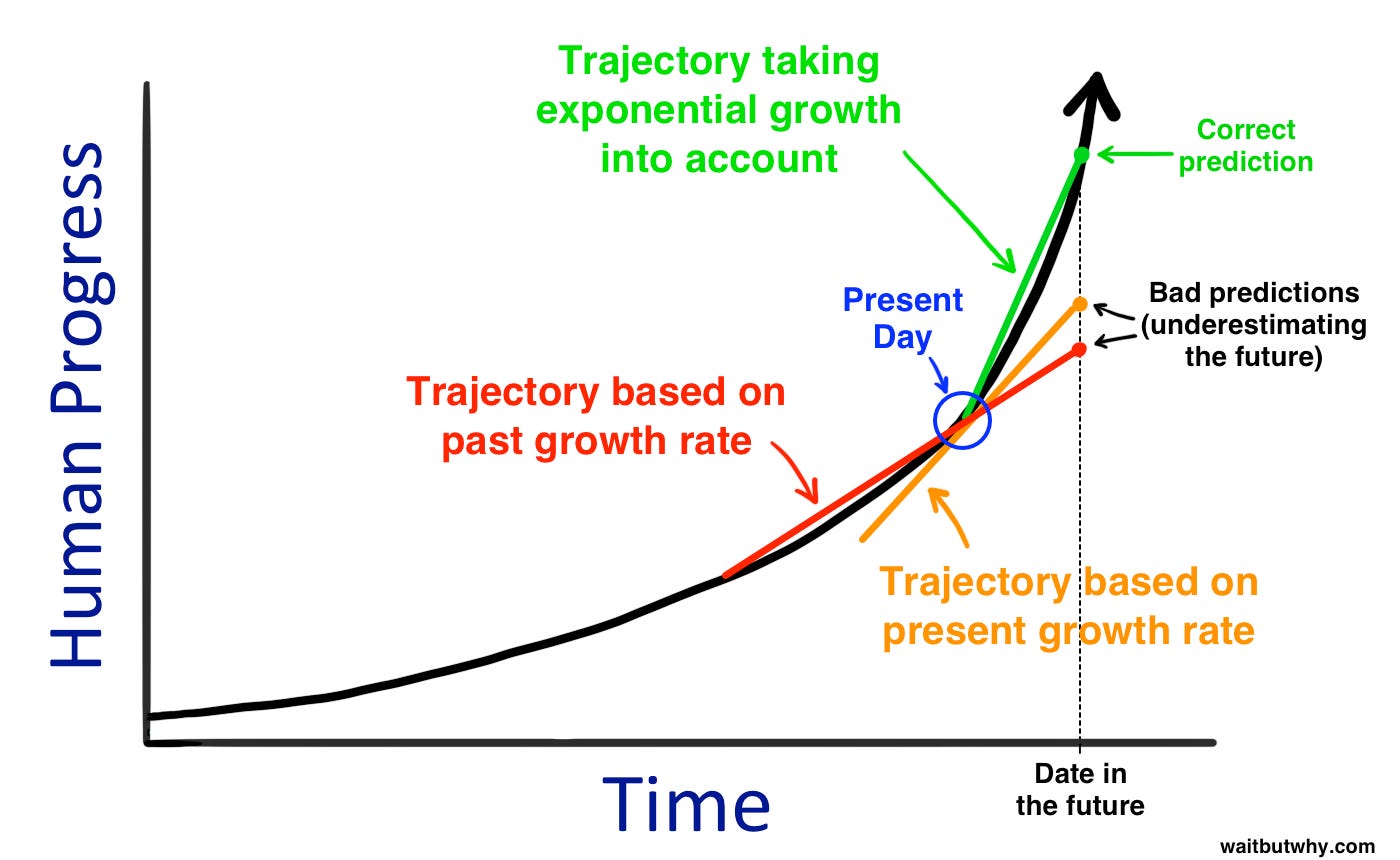

To clarify; I do believe in the notion of technological advancement, but would side with Thelian Great Stagnation thesis that not much has happened since the seventies (except for the computers), rather than buying into the accelerationists’ narrative of exponential progress (pictured above).

The notion of progress with which I do not agree with is the evolution of humans towards something better or greater (unfortunately). I go as far as The Enlightenment to elaborate on this point.

Burniske describes markets as "a powerful technology that is meant to serve society’s virtues, but markets are dangerous as a virtue system in-and-of themselves". He believes that markets dictate our virtues, calling for designing blockchain protocols that embed better virtue systems [0].

The actual blank slate of state refers to a unique opportunity for "a new way to organize humans, to orchestrate the movement of value according to our virtues...a potential fresh start."

Burniske is worried that the crypto community fails in building a fairer, effective and generative system - the values he personally thinks should be reflected in the new market protocol. He writes that investors and founders "claim too much of a network’s capital for themselves, they are taking the lessons of an unfair past and projecting them into the future."

My worry is that this essay reflects a flawed belief of a broader set of influential entities in crypto (and tech). This is why I have taken to address what I consider to be a dangerous line of thought.

First, I would like to address two deeply problematic assumptions that Burniske makes. These are foundational mistakes in his further evaluation. One is the notion of progress and the other is conflating market and virtues.

Second, I will present an alternative take on how crypto becomes valuable and what I think it can actually deliver in the future.

Progress and The Cornucopians

In True Detective series there is a scene where a father-in-law of one of the main characters complains about the young people, asking the younger counterpart Marty:

"So you're telling me the world is not getting worse?"

Marty replies:

"You know, throughout history, I bet every old man probably said the same thing. And old men die. And the world keeps spinning."

This moment is an elaborate version of the "Ok boomer" meme. The youth is vindicated in this great comeback line. The old man's point has been invalidated.

Joe Rogan has his own version of "Ok boomer" rebuttal, often remarking that life on earth has never been better before. This reminds me of a belief "that all history is a halting and imperfect preparation for the magnificent era of which we are the salt and summit"[1].

People make the same mistake both ways. What if I redpilled you that the world is not getting better or worse? "The motto of history should run: Eadem, sed aliter." [2] The more things change, the more they remain the same and

...we shall leave the world as foolish and wicked as we found it. [3]

Progress, as described by some technologists (and some economists), is mostly a false idea. This belief is built on two axioms:

We can increasingly explain more of the world

The world is getting better

Nassim Taleb describes what he calls a modern disease; "the pathology of thinking that the world in which we live is more understandable, more explainable, and therefore more predictable than it actually is".

At all times men throughout history believed that they can explain the world. Every time they have been proven wrong in the future. Why are we so arrogant that we think we are so different that NOW we can solve one the oldest problems in human history?

We like to tell stories and create narratives. It is a human instinct to "give meaning to all manner of shapes; we detect human figures in inkblots" [4]. Our mind recognizes a pattern, abstracts a made-up metric, and creates a narrative. Some narratives are better, have better storytellers and last longer than others.

Think of GDP. One can interpret GDP as a metric abstracted from a human observed pattern turned into a narrative of never ending growth [5]. The pattern eventually does not hold and must be tinkered with to last a little longer [6]. The metric of GDP becomes a procrustean bed that is designed to play into the growth narrative.

Steve Pinker is an avid advocate of the idea of the ever-improving world. He has tried to demonstrate that there has been less violence in modern times. Unfortunately, this has been debunked as an ignorance of statistics [7]:

There is no statistical basis to claim that “times are different” owing to the long inter-arrivaltimes between conflicts; there is no basis to discuss any “trend”, and no scientific basis for narratives about change in risk.

John Gray has devoted volumes disputing the modern notion of progress. He attacks the claim that accumulation of knowledge and technological advance set us free. On the contrary, Gray claims, it traps us as we have to organize ourselves around this newly found idol (artificial outellignece flashback).

Burniske's essay is a play at the Hegelian idea of the end of history, a utopian end-game of civilization. Also, it paints a Pinkerian picture of ever-improving human condition and the undeniable road to this utopia.

As Peter Theil would say; the problem is that if you're so sure about the inevitability of your destination, the exact plans on how to get there become an obscurity.

The world cannot be explained by extreme pessimism of the old man's cranky complaint about the world going to hell. Nor can it be explained by an extreme optimism depicted in the exponential progress narrative.

Both extreme optimism and pessimism lead to passivity. We should think of the world in a state of becoming - not getting worse or better.

Markets and Virtues

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. This cliche teaches us to separate an intention from the outcome. The socialist thinkers meant well. Sometimes good intentions of virtuous people lead to catastrophes.

Burniske describes markets as "a powerful technology that is meant to serve society’s virtues, but markets are dangerous as a virtue system in-and-of themselves". He believes that markets deploy our virtues at scale, calling for designing blockchain protocols that embed better virtue systems.

It is a fundamental error to think of markets as a mechanism that portrays the world as it ought to be [8]. Markets merely portray the world as it is, communicating information of particular circumstances of time and place via the compiling mechanism of price signals [9].

Markets are the best means of reliable delivering information about "what is". Virtues and virtue systems such as religion are best at describing what "ought to be". If the market does not reflect certain virtues it is because these are absent (in aggregate, not individually).

The idea that we can encode virtues into the market is absurd as virtues do not scale [10]. One cannot ignore the scale transformation property, the wedge between intentions and outcome, as "one does not necessarily build a virtuous political system with virtuous agents. Likewise a collection of malicious agents can produce a virtuous system" [11].

Say that the virtues an average German citizen of 1930s and 40s aspired to were hard work and patriotism. I sincerely doubt that an average German citizen of the time would voluntarily sign off on a mass murder. The scale transformation property of such virtues on the individual level appointed a sociopathic and egomaniacal leadership prone to mass murder.

We should remain cautious when discussing virtues because "that which men call virtue is usually no more than a phantom formed by our passions, to which one gives an honest name in order to do with impunity whatever one wishes" [12].

Burniske thinks of markets as a reflection of our own design, therefore; he wants us to be careful with the design. To be more specific; he would argue that destruction of natural capital should be accounted for. A decision to encode "cost of nature" into the universal accounting system would come from a place of virtues.

I do not consider the market a product of human design but rather a natural information compiler. Markets are a complex consensus mechanism that does not respond well to human intervention because it introduces subjectivity. Subjectivity cannot be computed. Therefore; I do not believe we can change the nature of the market.

Markets are amoral. One has to feed them numbers. Think of markets as a black box software protocol to which repo we have lost the access key. Somehow we have to keep using it without fully understanding it.

Virtues are a function of morality that cannot be reduced to numbers. One can try to fight the market with applied morality but this tends to backfire due to the scale transformation property. This is a mere reflection on the traditional notion of separating the intention and the outcome.

Is Crypto Programming People?

Burniske's idea that "technology enables us to program behaviors" could be misleading. Technology enables a modification of agent's behavior. A claim that we could program behaviours is a hyperbole.

Technology enables social scalability by moving information from mind to a computer chip and directly improve matchmaking abilities through Uber, Facebook or AirBnb and minimizes trust requirements with programmable value [13]. But trust minimization or improved discoverability do not guarantee the behavior of agents entirely.

Bitcoin and Ethereum enabled monetary and financial coordination at scale by encoding incentives into the protocol. It does not predict the behavior of agents entirely. Only in certain aspects we have achieved modification, therefore; we have to be careful about implying that we can program (and predict) behavior of agents entirely.

With technology we can achieve certain modifications in agents' behavior, thereby reducing a particular trust uncertainty. By reducing trust uncertainty we reduce certain market friction. But we have not mastered human nature. Here, the technologists' utopia converges on the political utopia (e.g. communism).

In my view Burniske's essay displays a desire for a predictable world where behavior can be controlled. This is further projected onto expectations about cryptoassets and their potential.

Programmable Value

Programmable moneys and the programmable internet of value is a huge step forward in terms of social scalability. I do not contest that. By programming attributes of virtual assets we do achieve a modification in human behavior.

I have written about programmable money as a form of artificial outelligence, in which I do acknowledge the element of programming behavior of agents participating in the system.

However, I would not suggest that human behavior is predictable when confronted with programmable money. What can be predicted is that the behavior will be altered in some way.

We have successfully reduced complexity of the world to a game. But still, the actions of agents cannot be precisely predicted, although some aspects of behavior can be game-theoretically guaranteed.

Programmable value is a leap forward. Society will gradually come to harness the property of being able to organize itself around hard(coded) systems. I personally believe that we are on a (bumpy) road to non-discretionary money and that, perhaps, at some point it the existence of these assets ensure continuity of civilization instead of disintegration into chaos.

The World Will Not Change Much / Crypto Is Here to Stay

In alignment with the "progress as a myth" thesis, one should not expect that much will change with the advent of programmable value. What will change is that value will be embedded into the digital - the world of mathematical logic it actually belongs to [14].

A world from which we had to abstract it for a couple of thousands years and import it into the physical; shells, coins, gold and other SoV. This import is prone to manipulation. Thus, one could expect that we will move from the world of reserve currencies to a fluid programmable value, embedding value back to the logical world of zeros and ones.

But as I have discussed above, fairness and goodness cannot be reduced to numbers. Markets do not deal with abstracts. Can blockchains deal with them?

Burniske would say that we can encode e.g. the cost of nature into the accounting layer. This is possible. However, I am not sure if it is desirable. Blockchain's accounting layer does not only rely on trust-minimization but also on subjectivity-minimization [15]. Cost of nature, may not be universally accepted (think developing world), although we might be able to agree that it would be universally a good thing.

Burniske explains that we could use blockchains to involve more people in capital accrual and governance - a more fair distribution. But what is fair? Is it a more egalitarian distribution? Does it mean more rich people or less poor people? Does it mean to embrace downward mobility for the rich or upward mobility for the poor?

The side-effect of a generously expanding monetary base is that it allows capital to accrue more capital with labor falling behind. It is a feature of such a system not a bug. Unleashing blockchains within such a system is more likely to do the opposite and thus let the power law dominate.

One cannot discount the possibility of programmable money contributing to even more pronounced long tail distribution [16]. I failed to understand what Burniske's fair means. Is manifestation of power law unfair? Is inequity unfair? - Certainly under particular moral axioms.

I would like to believe that blockchains could allow more people to access more markets in more ways and if Burniske means "more of equality of opportunity” I agree. But it is worth considering whether more of equality in opportunity can lead to greater inequality in outcome.

Still, as the system remains anchored to discretionary value, it will probably prop up the existing hierarchy of capital. What we can hope for is that eventually the interface to the market becoming purer.

Revanchists and Progressives

There are still things to discover and novelty machines to build. More importantly, technologies could be used to implement redundancies instead of mere over-optimization of systems. Nic Carter argues that Bitcoin is a revanchist/restorative technology not a progressive one.

This led me to frame Ethereum as a progressive asset in contrast to Bitcoin. It should be of no surprise that if this framing reflects the reality, the advocates of these two respective technologies (and assets) are inevitably clashing.

Tribalism in crypto is not necessarily a bad thing, and lamenting the conflicts between these tribes is a symptom of fundamental misunderstanding of either what these trends represent, or the function of tribalism.

Both of these communities agree that the status quo is unacceptable but their approach to overcoming it is vastly different. One argues for "building the future", while the other calls for a revision of the past. One is fundamentally optimistic, the other seems fundamentally pessimistic about the future.

The philosophies of these groups are naturally rivalrous yet their success is not mutually exclusive (at least not in the short-term). The usefulness of such compartmentalization is also limited in the long-run, but comes in handy when telling the motives of the tribes apart.

Although Burniske has since course-corrected his stance on the topic, he has outrightly disapproved of tribalism in crypto in the past [17]. Eric Weinstein points out that the negative/positive notion of tribalism is context dependent.

Adaptive tribalism is an evolutionary way to bootstrap things and is comparable to the notion of localism. Tribalism is not bad. Tribalism is human. Therefore; we are observing fluctuations in tribalism throughout the history. Becoming less or more tribal is not a sign of progress.

Humans will remain tribal. Does tribalism in crypto extend itself beyond its usefulness? It may be. But it demonstrates how some things stay the same the more they change. The future may look like the 60s with a design overhaul (hopefully with similar attitudes of doing not talking).

Humans Are Not Machines, Machines Are Not Humans / Beyond Rationality

Chris Burniske is probably right in that in programmable assets we may eventually find a better way to coordinate and distribute value between participants. But the idea that the future is exponential and more fair is less right. As stated before, the future will mostly resemble the imperfect past.

It seems that in most technological and political visions achieving a fairer system is predicated on abandoning much of the human agency [18]. Most fairness-oriented belief systems are predicated on centralization doctrine. The technologists' version of this is a reference to the Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

Some people long for machines with human features (AGI), while desiring that they themselves were more like a machine - a system of predictable interactions. They project onto machines the desire to have human properties, while themselves desiring to have properties of a machine.

In their version of the future, humans become a machine; a system of predictable interactions that are under control or can be fixed by mechanical intervention.

Our pop-culture fantasizes about AGI taking over the human race, attaching the unpredictability of human agency to, by definition, a predictable machine. We make movies about AI with feelings. Some of the technologists' visions resemble Nietzsche's last men.

We project once desirable human traits on the machine. This is an act of humans who are afraid of themselves. They fear confronting their true violent inner selves. But why would humans be afraid of themselves?

This could go as far as the birth of the Enlightenment, which is embodied in a reference to liberalism in Burniske's essay:

Liberalism unlocked the rational individual in free markets, the ideological key that released society from feudalism. A good thing.

Indeed a good thing. But there were costs attached to this liberation.

In Straussian Moment, Peter Thiel describes how Enlightenment had become a new platform for stability after years of religious warfare in Europe as

the enlightenment undertook a major strategic retreat...The question of human nature was abandoned because it is too perilous a question to debate...Science of economics and the practice of capitalism filled the vacuum.

Whitewashing violence has been a founding myth of Enlightenment, strategically ruling out the questions of human nature, reducing human to homo economicus, and his desires; to desire to power [19]. Is it a coincidence that Burniske has chosen a reference to a Blank Slate - the very origin of the denial of human nature?

One could think of Enlightenment as a cheat code. Cheat codes can take out the thrill and fun out of the game, but they help you win comfortably. In a world where the "thrill and fun" is actual suffering and death, resorting to a cheat code is understandable. But one is not playing the real game anymore.

The cheat code gives us the illusion that we have mastered the game and that we are in control. The more control we try to exert on the system the more we deny human nature. It scares us. And rightly so.

Different belief systems have different coping mechanisms to face the fear. Progressives try to control the system, libertarians try to control what is theirs. The desire for control in any sense stems from the actual recognition of human nature - there is something to be feared.

The Return of The State

In the beginning I mentioned the "Thielian moment"; a culmination of tech cornucopia narrative reckoning with the fact that progress is neither unconditional nor real. In recent decades we have been dressing up numbers as progress and such quantification (and over-financialization [20]) distorts the reality in an attempt to mislead us a little longer.

The strategy we have devised can be summarized as: I reject the reality, I create my own, with an example below:

According to Thiel, this is the hallmark of a great shift to inward-facing culture; psychedelics, video games, VR, artificial elements of zen etc. Perhaps the pendulum had swung from interior to exterior since the Enlightenment and sometime in the 1970s it started swinging back.

He states this clearly; "No representation of reality ever is the same as reality...The price of abandoning oneself to such an artificial representation is always too high", and cites Schmitt:

Men who allow themselves to be deceived by him see only the fabulous effect, nature seems to be overcome, the age of security dawns; everything has been taken care of, a clever foresight and planning replace Providence.

Hence the “Thelian moment”.

We have entered a somewhat blank state of our existence, submitting to either utopian or dystopian visions of the future. Either way, we seek refuge outside of human agency in the arms of the almighty state - whether it is a technology or the government.

Is it really that different to look for virtues in state-machines or in the actual state backed by monopoly on violence? State and technology does not contain virtues.

But they contain violence; in both senses of the word.

I very much appreciate Chris Burniske's input, helping me to better understand his thoughts around this topic. Although @fiskantes accused me of sophistry I believe that this is a result of a displaced unhealthy attachment to videogames. I still thank him for his valuable inputs and trolling as he is gradually becoming my personal editor. Furthermore I'd like to acknowledge thoughtful feedback from @thegostep and @allenf32 .

References & Notes

[0] @allenf32 understood Burniske's point as “when markets work super well we focus too much on their outputs and not their throughputs, a kind of implicit Goodhart's law”. This begins as a seemingly valid criticism that later becomes misunderstood when Burniske proposes that we need a market mechanisms which have outputs that we as a society can approve of more. But how do we agree which virtues to approve?

[1] Will Durant (paraphrasing Schopenhauer) in The Story of Philosophy

[2] Arthur Schopenhauer

[3] The Wisdom of Life by Arthur Schopenhauer

[4] Nassim Taleb; Fooled by Randomness

[5] It is relatively easy to lie about the rate of technological progress as you take liberty with interpretation of data.

[6] A reference to Boskin Commission. In mid-90s jiggling with inflation numbers led to reduction in inflation rate by 1.1%; thereby saving trillion of USD over a decade and balance the budget.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1997/04/how-to-rewrite-economic-history/376830/

[7] @fiskantes proposed not to involve statistics but a simple skin-in-the-game heuristics; if you had choice 1. "Be born today" 2. "Be born at a random time in the past 10k years" . Which one would you choose? This is a valid proposition, however, to do this right one should do this survey in every time period. If one chooses present times it could be because that is all one knows (a hypothetical present-bias) . My goal was to cast doubt on Pinkerian hypothesis which is based on statistics by referring to a study that suggests employment of "bad statistics" on Pinker's side.

[8] Eliezer Yudkowsky in Inadequate Equilibria: "People have an innate understanding of ‘true’ in the sense of a map that reflects the territory, and they can imagine processes that produce good maps… People understand that efficient prices means that people ought to be paid $9/h or that by saying ‘efficient’ this econ/math machine is right about $9/h being good for society, the price justly reflecting someone’s effort...‘they hear you agreeing with the pitiless machine’s judgement..."

[9] Hayek in The Use of Knowledge in Society: ‘We make constant use of formulas, symbols, and rules whose meaning we do not understand and through the use of which we avail ourselves of the assistance of knowledge which individually we do not possess.’

[10] Taleb in Principia Politica, Principle VI: "Group morality is not the sum of individual morality. Never make moral inferences about an aggregate or a group from attributes of individual members and vice versa. Under adequate legal and institutional structure,the intentions and morality of individual agents does not aggregate to groups. And the reverse: attributes of groups do not map to those of agents."

[11] Nassim Taleb, Principia Politica

[12] La Rochefoucauld

[13] Nick Szabo's Social Scalability

[14] As per Eric Weinstein we can use digital and logical interchangeably. I can speculate here that value is an organic part of the logical world (that is; the digital, limited to the zeros and ones). Since in the past we had no means of recording things in the digital world, we had to import value into the physical world; shells, coins, gold and other SoV. Such import is imperfect and prone to manipulation. Programmable money embeds value back to the logical world.

[15] This would lead us down the rabbit hole of Blockchain governance (governance-minimization vs. maximization).

[16] We have witnessed that the IT revolution created a lot of wealth with products beyond the world of atoms (software). The previous revolutions (e.g. oil) the goods and services were still subject to the physical realm with value capture enabled locally. The distribution of wealth in a borderless digital world is a subject to power law. Local extraction of value is limited.

[17] To clarify; Chris Burniske no longer agrees with his past tweet and is ok with the interpretation of tribalism presented in this essay, "alas, Tweets are static."

[18] In what way is China and Silicon Valley similar? - They do not believe humans can decide for themselves.

[19] Peter Thiel in Straussian Moment

[20] Thiel argues that "finance epitomizes indefinite thinking because it’s the only way to make money when you have no idea how to create wealth" (or build the future). Maybe we’re not attracted to finance but there is not much left to do because going further requires us to revisit the game beyond the cheat code? Finance has the ability to stay divorced from reality for a very long time, syncing only on occasions in the moments of sanity, which occur when economic bubbles burst.